Sonder-Core and Other Thoughts

A conversation with Gareth Damian-Martin prompts an introspective look at video games as a whole.

I wish there was a better way to sigh onto a page than by merely typing the word surrounded by asterisks. There ought to be something more evocative, yet similar in brevity. I would open this post with this new made up onomatopoeic sound, were it available to me. It seems, despite my best efforts, or misplaced confidence, or some sick and worrying combination of both, I am only able to take a single step forward, followed by several sliding steps backwards. Having a desire to write about video games on a deep level is, as it happens, cost ineffective to maintaining the mental bubble I’ve created to weather the miasma swirling about. It’s so fucking frustrating. If I turn on my thinking brain to write, I have to ward off the demons of the world? What kind of bullshit is that?

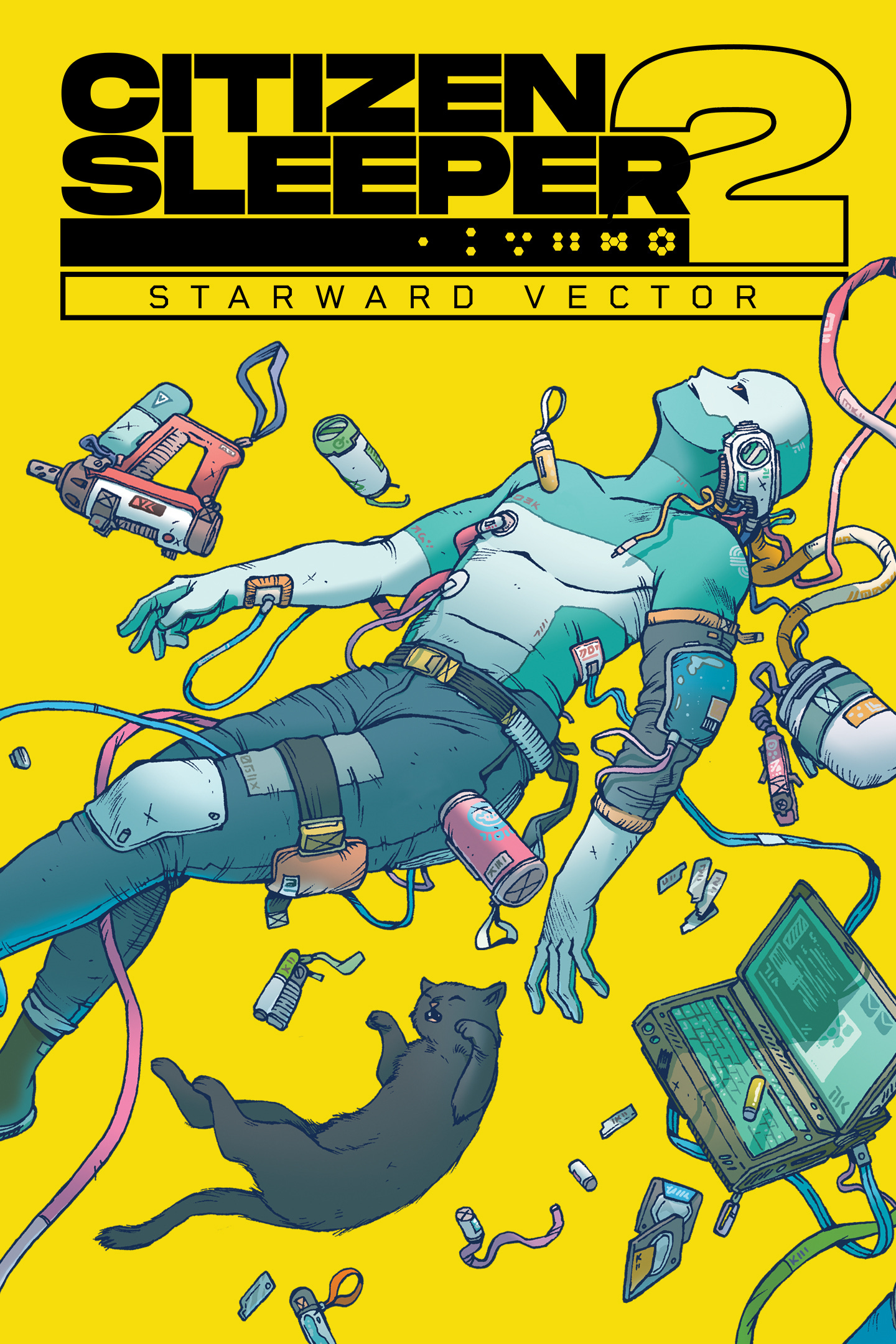

A few months ago I played through Citizen Sleeper 2. In the closing hours of the game the winter weather brought dry, drifting snow, covering my city (and by extension, block) in sharply rolling, steely glistening dunes. The concrete was cold, so the snow left striations along the even ground, giving the illusion of rippling, but still water. I often sit on my porch past 2 in the morning, wrapped in coats and hats, fingers sneaking out from my sleeves to pinch a cigarette to my lips. Finishing CS2 with the silent staccato of cigarette breaks punctuated my experience. The game, taking place on a ship in a tumultuous galaxy, tasking the player with navigating from safe harbor to safe harbor, all while taking on the troubles of the folks in each location, paired perfectly with the piercing cold. The silence. The creaks of long dormant trees.

In my conversation with CS2’s creator Gareth Damian-Martin, we stumbled into a bit of linguistic revelation. I mentioned the game’s relationship, more proximity, to the concept of sonder, a word I discovered in college and have found deeply grounding.

Defined, sonder is: The profound feeling of realizing that everyone, including strangers passing on the street, has a life as complex as one’s own, which they are constantly living despite one’s personal lack of awareness of it.

It’s a bit wordy, but perfect. Every passing car, every lit window on the horizon at dusk, every jogger, dog walker, or cyclist, every coffee shop patron is living a life as full of complications and stressors as my own. A constant reminder that every conversation I pass amid-sentence is laced with the intentionality and emotion of the person speaking, and is dependent on the participation of the partner being spoken to. I think sonder leads to empathy. It draws your own experience away from the focus and pulls this rapidly moving machine of humanity into the center. Gareth’s games remind me of this. Each character cares about their work, worries about their loved ones, drives toward personal goals, and I feel it in each of them. A testament to Gareth’s writing ability, surely. But perhaps also a compliment of their ability to create real and tangible. Or perhaps just reflect them. But the revelation in our conversation came when I realized they had never heard of this word. I got to share this with a person I deeply admire. What’s more, I got to sit in silence as they mulled the word over, chewed it in their minds, and realized they did, in fact, deeply connect with this concept. And then, as easily as my kids bring joy, Gareth described their work as “a sort of sonder-core” experience.

I have not recovered.

What I have done, in the stead of recovery, is look backwards at all of the games I have ever played and investigated my motive in each of those experiences. I exaggerate, of course, but the work has been constant. What I have found is the echoes of sonder in everything. Wandering the wilds of Star Wars Outlaws, constantly pondering the lives of the people passing by. The intensity of a match of THE FINALS, thinking about the person on the other side of the gamertag ticking across the screen. In the quiet fields of Gray Zone Warfare, questioning the absence of farmers and family pets. Pacing the temple steps in Japan in Assassin’s Creed Shadows, praying silently next to a mother and daughter. It’s everywhere.

It comes coupled with a particular type of loneliness. One I have become deeply attached to. One I experience on those late nights, sitting on my porch in the darkness, breathing smoke and thinking. Perhaps this is distinctly American, but there is such a disconnect between people and their world around them. I sit at the coffee shop and thousands of cars pass me in an afternoon. Each and every one of them with drivers and often passengers, all humans, enduring life. Hopefully enjoying it. I sit, though, in silence. Sometimes I listen to music. It makes me wonder: how many people never consider the lives of those they brush shoulders with? How many emotional deficiencies could be counteracted by simply acknowledging the existence of everyone, everything around us? How many people play games and never conceptualize the lives of the NPCs milling about in the background?

One of the first things I read, back when I was getting started, was a piece written by Austin Walker for Paste. The article debates the morality of killing NPCs in games, as developers become more and more capable of making them feel more and more real. A messy and imprecise summary, honestly, but the meat of the matter stuck with me, causing me to constantly question myself when engaging in virtual violence. In the ten plus years since Austin wrote this piece the problem has truly only grown more complex. Watch Dogs Legion gave each person you see in London schedules and family members and likes and dislikes. I remember the moment I came across someone I couldn’t recruit because I had struck and killed their brother with a car. I followed them for ten minutes. Stepped invisibly behind them as they left work and walked to the local pub. Was I the cause of the drinking? What would they think if they knew I was standing behind them, wringing my hands?

The same year I read Austin’s piece I had a perception altering experience playing Ghost Recon Wildlands. My friends and I have moved in on a small outpost of gang enforcers and were laying the groundwork for systematically eliminating them when one of us stepped a bit too far into the view of a character with a circle atop three horizontal lines over his head, the marker for the leader of the group. As he began to spot us we acted quickly and eliminated him, a few sharp coughs of suppressed 7.62 ammunition flew through his chest, depositing his mass swiftly onto the dirt beneath him. However, rather than the frantic gunfight we expected to break out, all the other gang members dropped their guns and surrendered. A game mechanic in action, surely. The leader taken out suddenly, the underlings abandoned their goals. Lines of code and playtested programming. But the implication, the suggestion it slipped under the door of my occupied mind caused me to pause. The game was ostensibly about a Mexican cartel invading Bolivia to commandeer their coca production. Fealty to gang lords in these situations had to be more coercive than volunteers right? Were these all just kids forced into the ranks of an invading force to protect their families? And by stealthily moving from outpost to outpost had we just been executing sons and brothers and fathers strong armed into service of cruel and violent enforcers? In that moment, how were we, the players, any better than them?

I try not to let my brain get too involved all the time. I am, however, very bad at limiting this kind of thought. So, rather inevitably, I return to this kind of inquisitive thought. It frequently makes me mad at games like Ready or Not, or Call of Duty, content with grounding everything in reality rather than being creative enough to create simulations devoid of human cost. But even then, Halo created a universe where, initially, you fought nameless and largely faceless alien monsters content with wiping humanity out, only to, in subsequent games, give those aliens both names and faces. The choice to make the Covenant a force assembled by religious zealots content with bending the truth so as to maintain their control over forcedly ignorant soldiers still remains a deeply inspired choice for a plot in the early years of our wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Does this mean it’s impossible to create games where violence remains the means of engagement without wading into muddy morality? Maybe? I am still a steadfast fan of Battlefield and numerous other shooters. Often I am capable of turning this part of my brain off. But my knowledge of sonder and its evidence that life is lived everywhere, all at once, regardless of our keenness to it, has made things…interesting. Violence in virtual spaces is cathartic, not just for myself. But the danger of thinking too much means the possibility of calling into question the motive of that same violence. Games like THE FINALS shift the perspective, making the competition a game show. Player characters erupt into piles of coins when they are eliminated. Extraction shooters, like ARC Raiders (by the same studio) allow for players to decide how they will interact with other players, even giving them the ability to help and revive others. I have more truck with this. It feels more organic. More real. Truly, one of Austin’s strongest points in his piece comes from his dissatisfaction with the limited toolset players are given to engage with. The response to seeing an NPC gunned down is never to stand beside them, trying to render aid or soothe those witness to the violence. Instead it is relegated to enacting compensatory violence. Perhaps it’s time to ask our games to do more. To give us more verbs than shoot, hit, break, throw, and kill.

Or, I guess, just give us more games about the Clone Troopers fighting Trade Federation Droids. Because fuck them. They’re just robots. Right?